Carolingian Cavalry: Combat Tactics and Training

Damien Schirrer • 23 décembre 2019

Carolingian cavalry: Tactics

Foreword

The Carolingian army makes extensive use of the horse, used during battles, but also for long trips during a military campaign. Aware of the importance of the horse in his army, Charlemagne legislates on the breeding of horses and their market value defined according to their specialization. It was common then that the "dona annualia aut tributa publica" which linked clerics and nobles to the emperor be paid in horses. The objective was of course for the central power to have as many mounts as possible and ultimately a large and powerful cavalry.

Shock Cavalry and Melee Cavalry

The Carolingian cavalry is divided into two categories. The first is a heavy and expensive heavy cavalry which was accessible only to large landowners (at least 12 manses). The second category consists of less fortunate horsemen who generally had only a horse, a shield and a spear of medium length, and formed a light cavalry corps. The existence of these two types of cavalry is suggested in the Annals "regni Francorum" of the year 782 which details the course of the battle of Süntal, opposing the Saxon army to the forces of Charlemagne. The equipment of the Carolingian cavalry is also described in the "capitulare missorum" of 792-793 and in a letter from Charlemagne addressed to Fulrad and dated 806. Finally the Carolingian iconography also seems to make a clear distinction between the heavy cavalry and light cavalry

Shock cavalry, equipped with heavy spears ("hastilia") and high-priced armor is as the name suggests predisposed to the charge. Given the weight of the rider and his equipment - which had to handicap the horse and restrict his mobility - it is likely that the charge of the cavalry of shock aimed at slower targets and if possible disorganized, as pedestrians or low-speed riders. .

Melee cavalry relies more on mobility. These men are equipped with a shield, a medium-sized spear, or a short "gladius / scramasaxe" type sword that unfortunately never equips cavalrymen in iconography, but whose use is mentioned in textual sources. This use of the "gladius" probably has to be seen as an alternative, used when the rider dismounts and rejoins a tight "phalanx" formation. The Carolingian rider is indeed trained to get on and off his horse as quickly as possible according to the turn of the battle

Walter's gesture: a precious witness

The account of Walther's gesture provides a detailed overview of the role that the melee cavalry played during a Carolingian battle.

- All clashes begin with a volley of missiles at the enemy. Archers and slingers are placed in front of the phalanx and copiously water the enemy with their features at the signal of trumpets ("classica") probably similar to those of the Utrecht Psalter. In Walther's gesture, riders also take part in this first phase of the battle: they approach enough enemy ranks to throw their javelins before retreating, possibly under the fire of their opponents. The interest of fixing the shield in the back by means of a strap takes here all its meaning, because it allows the rider to remain protected during his retirement. On rare occasions, we can observe in the iconography riders whose shield is thus fixed, freeing both hands and protecting the soldier from behind.

- In a second time, and once the ammunition exhausted, the riders reposition themselves in a tightened front, even in column, in anticipation of a possible load. Under the orders of a superior, and at the sound of the trumpets, the horsemen seize their swords and seize their shields (hitherto fixed on their backs).

- Then comes the load that requires the synchronization of all the jumpers, so that the frontal impact is as violent as possible.

In the case of a clash between riders, the power of the clash between the two opposing formations should not be as strong as what the author of the gesture of Walther tries to make believe. Indeed, the formulation he uses in the story ("the shoulders of some horses hit those of others, and some men fall to the ground") seems to be taken from a quote from Virgil. In addition, the short distance between the two formations generally does not allow the horses to reach their full speed. The text informs us, however, of the crucial role of the shield to disarm the opponent. No doubt that a violent blow carried by a umbo, or by the edge of the shield can destabilize a rider until causing his fall. We guess here the interest of equipping his horse stirrups (currents in the iconography) to gain stability in confrontations where the main objective is primarily to unseat the opponent more than to kill him while he is still in the saddle.

In the account of Walther's gesture, the battle ends with the retreat of the opposing forces, in totally disorganized ranks. Such a retreat could be accompanied by a signal given by a horn (or trumpet) as suggested by the iconography. Assured that it is not a "fictitious retreat" (of which we will detail the principle below), the hero Waltharius asks his troops to pursue their enemies as fast as they can, without the obligation to hold any training.

Example of large "trumpets" as they could have been used in major battles. Psautier d'Utrecht, folio 83r.

Archers mounted in the Carolingian army?

Charlemagne, in a letter dated 806 addressed to Fulrad, indicates that the bow is a weapon used regularly by the riders. This written testimony unfortunately remains anecdotal and few literary or iconographic sources enlighten us on this subject. The few horsemen armed with bows that can be observed in Carolingian manuscripts can indeed be inspired by ancient iconographic models or embody foreign peoples, such as the Avars, whom the Franks know very well. The horsemen, completely returned to their saddles of the Psalter of Stuttgart (to quote only him) evoke indeed the Asian populations which one finds sometimes represented on hunting scenes on the brocades of silk of Sassanide influence.

It is not excluded, however, that the Carolingians practiced archery on horseback, but it seems that it remained anecdotal. In any case, the use of the bow in the cavalry, if it is well controlled, proves very effective. It avoids losses and is very suitable for "retirement" tactics.

Carolingian Cavalry: Trainings and Tactics of the Fake Charge

Overview

The training and maintenance of riders is an expensive expense that most of the major European powers of the early Middle Ages must pay. Note that the intensive use of the horse in war is once again a heritage of the lower empire, shared by Byzantines and Carolingians.

Like pedestrians, an important part of the rider's training consists of learning how to maneuver in a group. Familiarizing the horse with the stress of the battle and the requirements of a group action greatly complicates the rider's training. His training usually spans several years. According to a no doubt ancient tradition, Raban Maur insists on the importance of training the rider ("equitem") from an early age.

The training of the rider, whether novice ("tirones") or soldier of career ("militia") requires knowing how to get on and off the horse as quickly as possible, depending on the circumstances of the battle. Raban Maur specifies that the training begins without armor, can complicate for the more experienced that one equips with a helmet, an armor and a shield, as well as a scramasaxe in its sheath, even of a long sword. No doubt that getting on or off a horse as quickly as possible implies a highly codified gesture, seen the weight and the clutter caused by such equipment.

Nithard, Charlemagne's nephew, described in detail in his book "Stories" the tactical training of the "feigned retreat" which was given to the troops of Charlemagne's time. Thus, according to him, two rider formations face each other at a distance of one hundred meters. At the signal given by the instructor, both groups throw the charge, during which the riders wave their spears, howl but stay in close rank. A few meters from the impact, one of the formations operates a sudden half-turn ("evadere simulabant"), feigning retirement, before turning around and engaging the fight with the help of dummy weapons or heavy spears ("hastilia") made of wood whose point is blunted. This millennial tactic, the origin of which may be Celtic and already described by Greek authors such as Arrian or Onosandre, was also used by the Roman army whose Carolingians were largely inspired. This training, which Nithard does not hide from the perilous nature, trains the riders in charge, but also in close combat with the constant concern to maintain a compact formation to maximize the damage caused during the charge. When soldiers pretend to retreat before resuming and flip-flopping, the main objective is to induce the opponent to break ranks to begin a disorganized pursuit and ultimately a suicidal charge.

In this tactic, the simultaneity of the shock matters more than the speed of charge itself. The disaster of the Battle of Mount Süntal is the perfect illustration: the heavy cavalry charged the Saxon forces at full speed without staying in formation and suffered a terrible military failure, forgotten (voluntarily?) Carolingian literature, with the exception of the Annales regni Francorum of the year 782.

Bibliography:

Butt John « Daily Life in the Age of Charlemagne »

Bachrach B. (2001) « Early Carolingian Warfare »

Coupland S. (1990) « Carolingian Arms and Armor in the Ninth Century »

Halphen L. « Eghinhard, vie de Charlemagne » (les classiques de l'histoire de France au Moyen-âge), ed Paris, 1923,

Devries Kelly (1987) « Wounds and Wound repair in medieval culture »:

Devries Kelly (1987) « Wounds and Wound repair in medieval culture »:

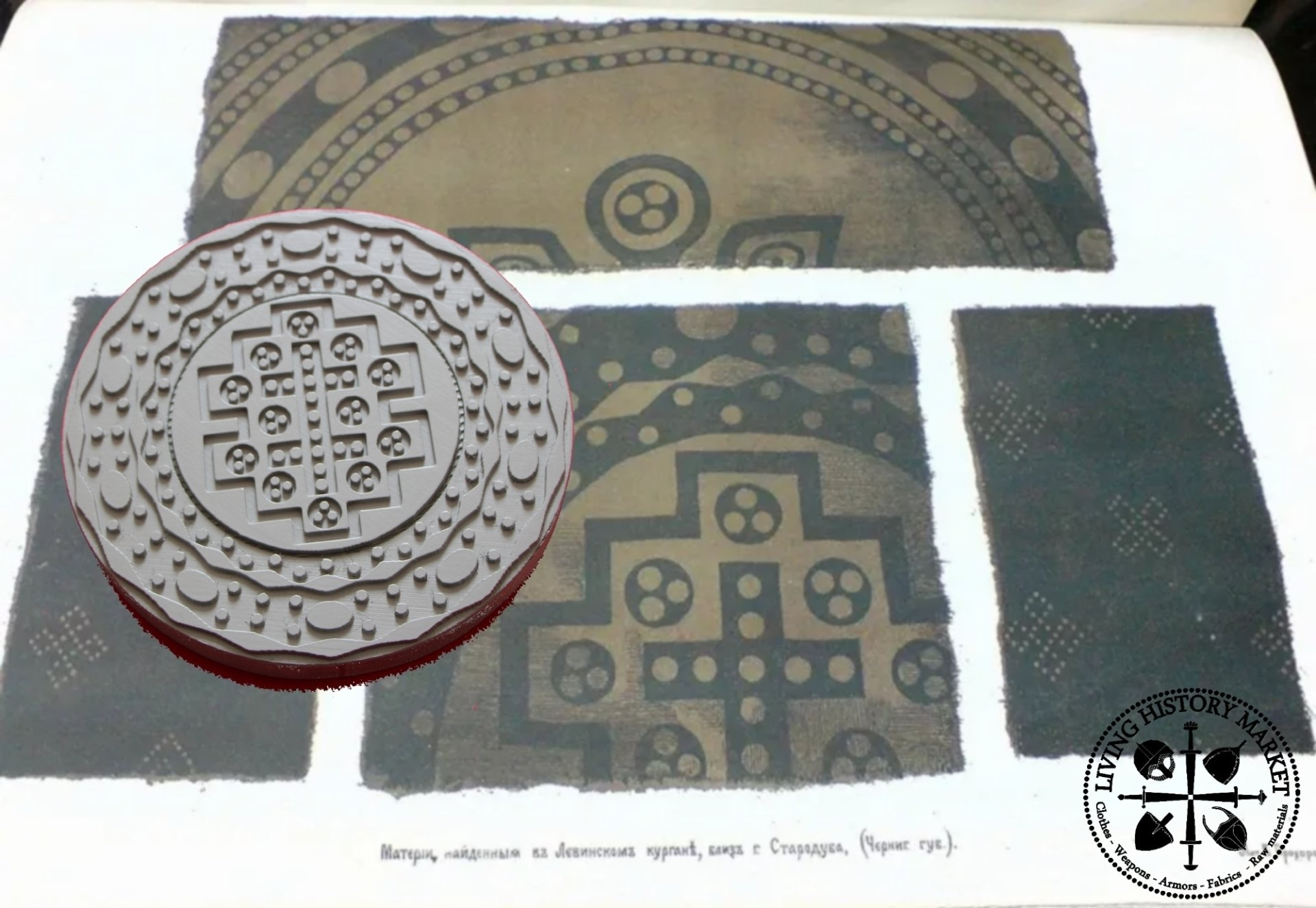

Les motifs tamponnés de Chernigov, qui sont au nombre de 2, sont connus de la grande majorité des reconstituteurs du début du moyen-âge à l'heure actuelle. La version « en croix » à décor crénelé, et l'autre, en « fleur » décorent désormais les vêtements de reconstituteurs de plus en plus nombreux, Rus, ou Byzantins pour la majorité. Les motifs tamponnés aujourd'hui, qui sont invariablement les mêmes, sont issus des travaux de E.S. Vidinova, datés des années 40. Cette interprétation quasi « unanime » à l'heure actuelle s'est faite sur la base d'artefacts fragmentaires, quoi que suffisants pour recréer un médaillon complet, par jeux de symétrie répétées.

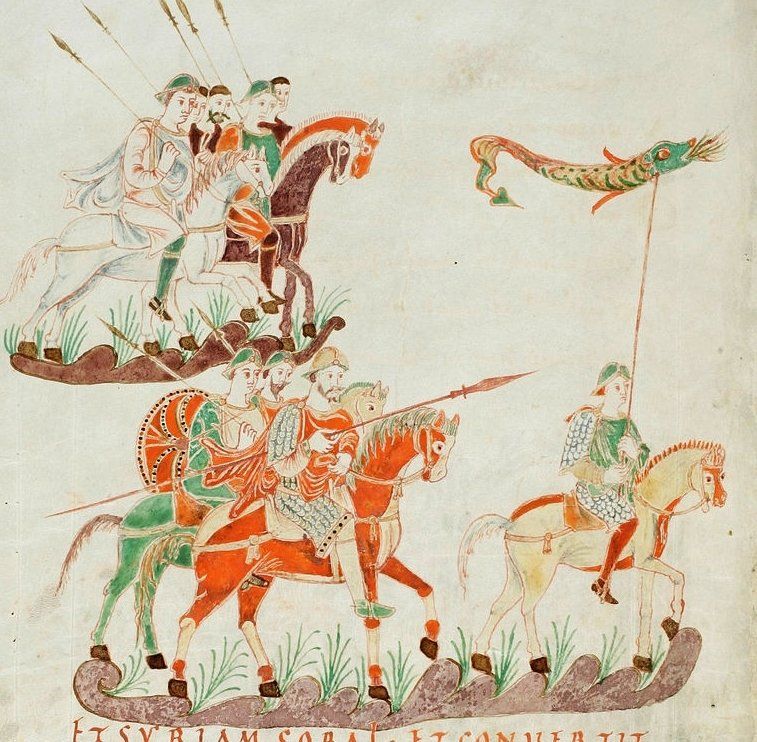

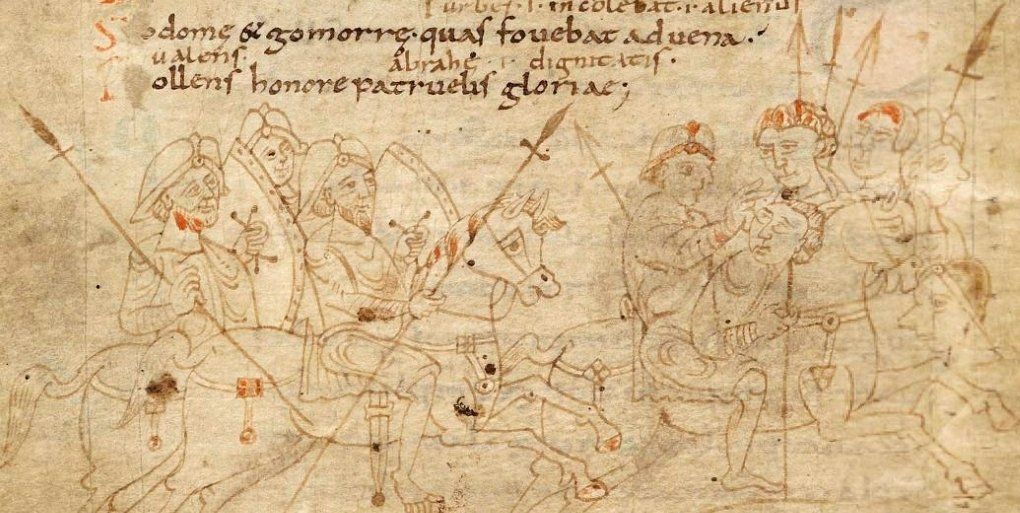

Origin and history of conservation This Codex, now in the Leiden Library in the Netherlands, is dated to the first half of the 10th century. It is therefore straddling between the extreme end of the Carolingian era, and the beginning of the Ottonian era. The construction of this work probably began at the Abbey of St. Gall, but seems to have been finalized at Reichenau Abbey in Germany. The manuscript contains the first book of "Maccabees" and the copy of the fourth book of "Epitoma Rei Militaris" of Vegetius. They were both assembled at the very end of the 12th century. Unfortunately, there is no digitization of the document in its entirety, and we will only be able to study scattered folios available on the Internet. Description of the content This Codex is famous for its formidable representations of bellicose scenes. The figurative events are biblical, but it seems that the, or the draftsmen, were inspired by Magyares incursions that ravaged southern Germany in the tenth century. Once again, and as is customary in Carolingian religious literature, contemporary material elements of the writing of the document are set on a narrative narrative relating older events. The stylistics of the drawing is particular, since it plays on the effects of compact accumulations of characters, preventing in fact any quantitative analysis where the basic unit is the individual. However, it is possible to identify with relative ease the represented militaria and to make cross-checks with available textual and archaeological data. The drawing of a rare delicacy offers valuable information on late Carolingian military equipment, and that of the Magyars, both mixed in scenes where soldiers are regularly arranged in combat formation. Analysis of military equipment Most warriors wear heavy chainmail, which is not usual in Carolingian iconography where scaled armor predominates. Perhaps it is due to the late nature of this document. Note, however, that some characters are protected from scalar armor already frequently encountered in the Stuttgart Psalter, written a hundred years earlier. The question of helmets, is quite difficult: About half of the helmets represented is similar in all respects to the helmets usually represented in Carolingian illuminations. They are reinforced with two crosspieces on the summit part, as well as another on the whole circumference: it is thus of "spangenhelms" all that is more classic. But the other half of the helmets has a tapered shape on the top and look in all respects to the helmet Pecs (Hungarian people, current Hungary, tenth century). It is possible to observe on the neck of the soldiers what could be a cover of chainmail or thick fabric, that Carolingians named "hasberga". Let us note that it is more prudent to abandon any hope of discovering in the Carolingian iconography any copy of a nasal helmet: Some reenactors rely on one or two helmets that have fallen to the ground, and believe that they see a nasal that is probably only a schematic representation of the chin strap, or the cover from the back of the helmet that fell to the ground. The shape of shields and umbos is quite classic. Note however the regular presence of oval-shaped shields without umbos, possibly of exogenous origin? For the rest, spears, javelins and swords are clearly visible, but the drawing does not allow to identify the typology accurately. We can also distinguish another element of more specific militaria, regularly represented in Carolingian iconography: the arc (composite, and of exogenous origin) with double curvature. Battle tactics Precious representations of phalanxes in compact formation can be seen in the Book of Maccabees. These men of humble condition are rarely represented in detail and deserve our full attention since they represented the backbone of the Carolingian and Ottonian army. These phalanges consist of soldiers grouped in tight formation, armed with a spear of medium length and protected from a shield. We will devote a whole article later to the operation of these phalanges, so much is it complex. At the option of the folios, riders ride in formation towards the opponent, ready to inflict violent blows with the help of the central umbo or the slice of the shield. The fugitives, also on horseback, wear their shields in the back with a strap to better protect themselves from projectiles. These scenes, of great wealth are witnesses of a tactic particularly appreciated by the Carolingian cavalry: the feigned retreat. Nithard, Charlemag's grandson , Count of Ponthieu and often struggling with the Scandinavians, went so far as to describe with precision this stratagem in his chronicles "Historia". This tactic is to charge the opponent, then, a few seconds before the shock, to simulate a retreat. The enemy, sure of his victory, may then start a disorganized pursuit. The attackers, on the run, of course, but still in formation, turn around and can surprise their pursuers whose ranks have been broken. In this tactic, training cohesion matters more than the load speed itself. The disaster of the Battle of Mount Süntal is the perfect illustration: the heavy free riders have loaded the Saxon forces at full speed without remaining in compact rows and suffered a terrible military failure, forgotten (voluntarily?) Carolingian literature , with the exception of the Annales regni Francorum of the year 782. Conclusion The Book of "Maccabees" is a source of great importance. Indeed, this Codex presents a military material, worn in real conditions (ie on a battlefield) as is rarely the case in Carolingian iconography. Therefore, it is possible to imagine more easily the use of the weapons and armor represented and the tactics employed on foot as on horseback. Finally, the drawing seems devoid of ancient influences, which frees us from the traditional questions relating to the origin of the represented militaria. Bibliography: Bachrach B. (2001) Early Carolingian Warfare Coupland S. (1990) "Carolingian Arms and Armor in the Ninth Century" Halphen L. "Eghinhard, life of Charlemagne" See also: Walther's Gesture. Author: Damien Schirrer.